|

Don and Jennifer's Family Site Charles Finkelman, Jr. |

|

Charles Finkelman, Jr.

"Charles" has been a popular name in the Finkelman / Fingleman family for a long time. The first "Finkelman" that we encountered in our research was in the 1860 Federal Census of Harris County, Texas, which enumerated "C. Finkelman" living in the home of Maximilian De Bajligethy and his wife Carlotta in Houston. Subsequently we learned that Maximilian De Bajligethy married Carlotta Finkelman (also known as Charlotte and Lottie), the daughter of Charles Finkelman, in 1854. We have explored the details of the Finkelman / Fingleman relationship in another article on this website, The Finkelman Connection, so we will not repeat that here, except to point out that there were also three young boys enumerated in the De Bajligethy home on this 1860 census, with the last name of Finkelman and first initials of "C", "A" and "L".

We now know that "A. Finkelman" was Don's great-grandfather August, who later changed the spelling of his last name to "Fingleman", and we know that "L. Finkelman" was August's brother Louis, who lived the rest of his life in Houston and attended August's funeral in Dayton many years later. We also know from August's death certificate that his father's name was Charles, and we have assumed that the "C. Finkelman" enumerated on this 1860 census was named Charles - the census record adds "Jr." to his name, indicating that he and his father shared the same name. We have been able to follow August and Louis through the years in official records and numerous other documents, and both August and Louis have many descendants. Most of those descendants alive today still live in southeast Texas. But until recently we have been unable to follow the life of "C. Finkelman, Jr." at all, and have discovered no descendants. Our quest to discover the destiny of Charles Finkelman, Jr. is now complete. Let us share with you what we found.

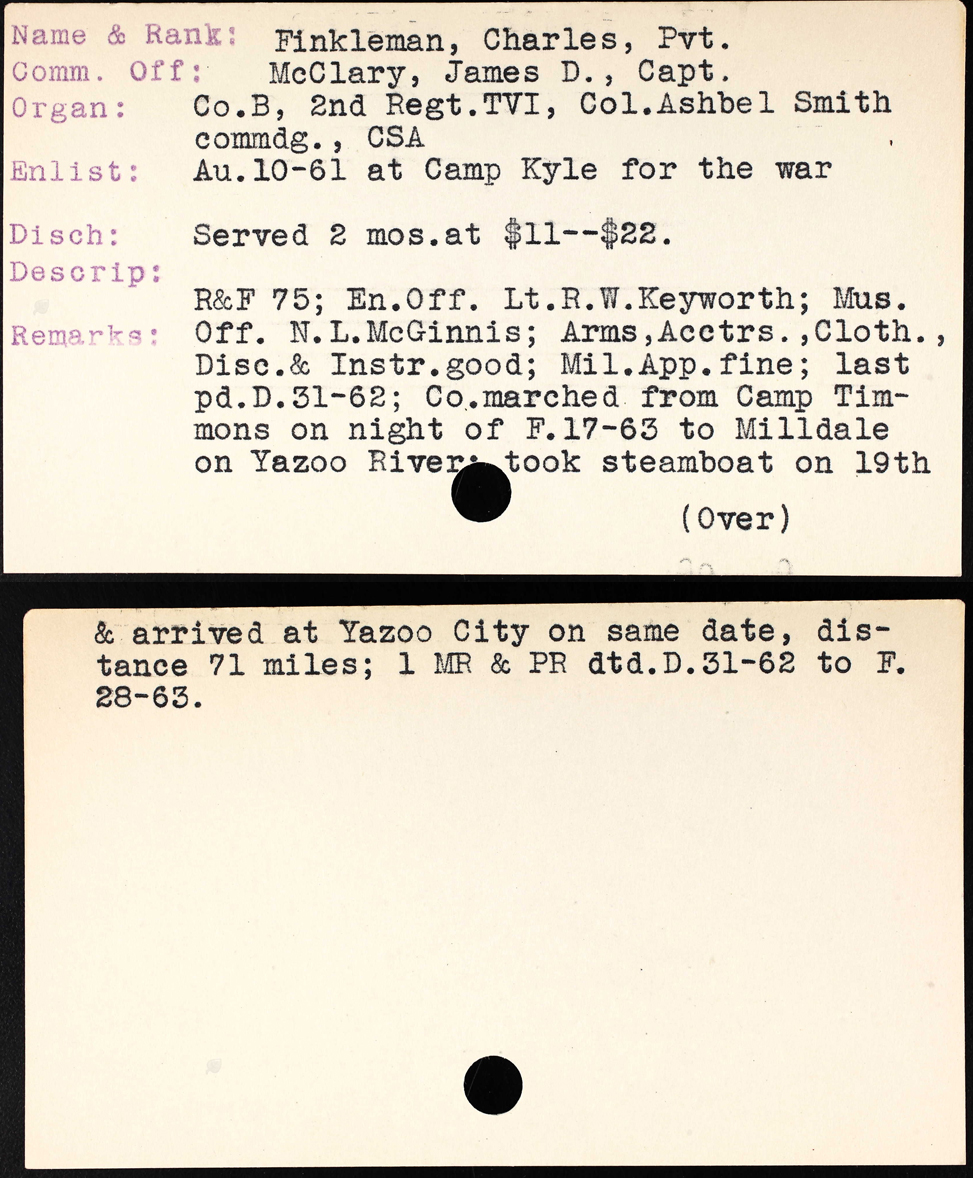

We found a service record for Private Charles Finkleman (last name spelled incorrectly), who enlisted in the Second Texas Volunteer Infantry Regiment on August 10, 1861. The Second TVI was formed in the Houston / Galveston area and commanded by Colonel Ashbel Smith, who was a physician residing in Houston before the Civil War. Charles' muster roll indicates that he arrived at his post on the Yazoo River near Vicksburg, Mississippi on February 19, 1863.

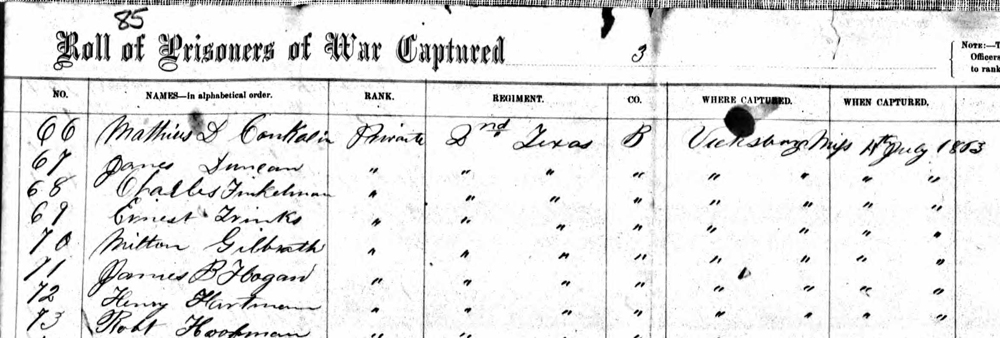

Then we found a record showing that Charles Finkelman (spelled correctly this time) of the Second Texas Infantry Regiment was captured on July 14, 1863 at Vicksburg and held as a prisoner of war. From other records we know that approximately 30,000 confederate soldiers were captured by the union army at the end of the Siege of Vicksburg, and that all were promptly released by General Grant on the condition that they return home and never take up arms against the United States again.

Next we found, in a book written by another early Houston resident, Dr. Samuel Oliver Young, titled True Stories Of Old Houston and Houstonians, another reference to Charles Finkelman. Dr. Young included in his book a chapter about night life in Houston following the civil war. On page 55 he writes: Whether the war was responsible for it or not, the fact remains that for several years after its close society was in somewhat of a chaotic condition and "most any old thing went," just so it was not outside the law. Men of fine social standing engaged in business that they would shun today, not because there is anything radically wrong with these things, but because they are now in the hands of professional people and are not considered just the things for business men of commercial and social standing to engage in. To illustrate what I mean I will state that the first organized vaudeville show ever in Houston was organized and managed, not by a professional showman, but by Ed Bremond, the son of the great railroad builder and capitalist. Just why Ed ever thought of such a thing no one knew, but he did think of it and he made a great success of it, too. That show was the "Academy of Music" and was one of the most popular places in Houston. It was located on the corner of Main and Prairie, upstairs, and was crowded every night. The next reference we found to Charles Finkelman is in the book The City of Houston, From Wilderness to Wonder by early Houston resident Dr. O. F. Allen. On page 17 of this book, Dr. Allen writes: In 1867 a number of youths, including the writer, organized a volunteer fire company known as Stonewall number three. Charles Finkelman was elected foreman and when this organization was completed the business men liked the idea and encouraged the boys by donating funds to help them purchase an obsolete hand-brake fire wagon.This was re-fitted, re-painted, and repaired and put in use. Not having funds to purchase horses to draw this large wagon, our twenty-five members would go into a run to a fire, each man holding to two ropes about thirty feet long, on either side of the front truck. We prided ourselves on beating the horse drawn engine when there was no mud, and we always did a good job when we reached the fire. Many times we would have to put the suction hose in a well in some ones back yard to obtain water.

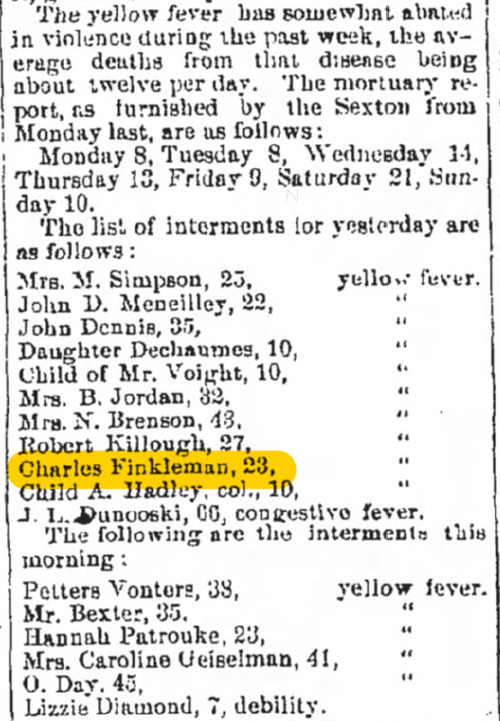

Finally, in The Galveston Daily News of October 9, 1867, we found this article, written by the Houston correspondent for the Daily News:

|